Reflections on Pittsburgh: Costa Rica Part Six

Sometimes you need to get away in order to see yourself more clearly. My trip to Costa Rica has put a few things in perspective for me, some of which I’ve written about already – how jails don’t need to look like the jails we have here, how people who are incarcerated can feel that their humanity is contested, and the challenges of balancing conservation with economic development. Recently I found myself as the keynote speaker in front of a group of Costa Ricans who were interested in learning how the Landforce model combines environmental stewardship and social justice. Once I got over the shock of seeing my face writ large on the poster for the conference, and figured out how to work with a simultaneous translator, I realized that in my presentation I would need to set the economic and social context for our City in order to explain why Landforce does what we do. Inevitably, it raised the question of who is able to call Pittsburgh a livable city, and touched on the question of equity and justice in Pittsburgh today. It pushed me to share some disturbing data about the Pittsburgh we all live in, but don’t all get to experience.

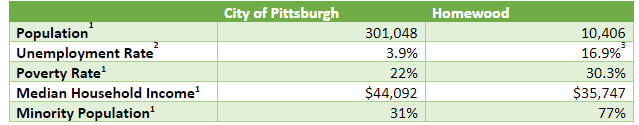

The question of “Most Livable City for Whom” comes up frequently in Pittsburgh, and the answer is clear – it is most livable for people like me and my family, based upon race, education level, and economic status (although for those who know my family, you will know that this is a somewhat complicated statement). For example, let’s look at a few numbers in the table below – the numbers in the middle refer to the entire City of Pittsburgh. The numbers on the right refer to one Pittsburgh neighborhood, Homewood. You’ll notice a great disparity in the unemployment rate, the poverty rate, and the median household income, with Homewood consistently “losing out” in comparison to the City in its entirety. What’s one of the most significant differences between the two? 31% of the people who live in the City of Pittsburgh are minorities, compared with 77% of those who live in Homewood.

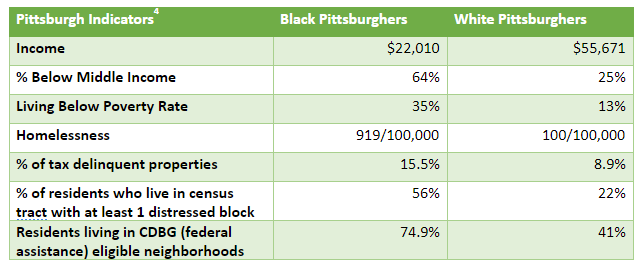

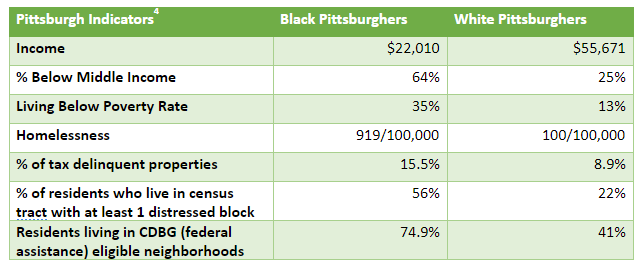

Data like this compels us to ask what the lived experience is in Pittsburgh’s minority neighborhoods. The annual Equity Indicator’s Report from the Mayor’s office showed an alarming gap between black Pittsburghers and white Pittsburghers. The next table shows that the average wage for black Pittsburghers is less than half that of white Pittsburghers, and the average wage of black Pittsburghers appears to be dropping. The percent of black Pittsburghers living below middle income and the percent living below the poverty rate are nearly 3 times as great as white Pittsburghers, and black Pittsburghers are 9 times more likely to be homeless. The poverty felt in Pittsburgh’s black households carries over into the neighborhoods where people live and spend their time — if you are an African American Pittsburgher you are nearly 3 times more likely to live in a census tract with at least 1 distressed block and twice as likely to live in a CDBG (federal funding) eligible neighborhood. This carries over to the workforce – 11.4% of Pittsburgh’s male population is African American, but makes up only 5.4% of the region’s adult male workforce. And this last figure makes my head explode every time I see it — 51% of people who are admitted to the Allegheny County jail are black, but African Americans make up only 13% of the county’s population.

This injustice extends to the physical spaces we inhabit – in poorer communities there tends to be a preponderance of vacant lots; parks and playgrounds that are older, more poorly maintained, or just don’t exist; abandoned houses and storefronts that are crumbling and unsafe; fewer trees; and higher levels of lead and other pollutants in the soil, air, and water. And because we tend to have policies in the USA that over the years have created and reinforced racial segregation, black Pittsburghers are often more significantly affected by these deteriorating spaces. And as we all know, this is not just a Pittsburgh phenomenon, but exists throughout the USA.

About half way through my talk, I realized how it must sound, as an emissary from the United States (and since this was a State Department funded visit, that is, inevitably, what I was), dishing dirt on the U.S. city in which I lived. I stopped, acknowledged the irony, and explained that Pittsburgh is a place that I have grown to love, and when you love someone or something you want them to be the best that they can be. When I told my husband this story, he asked, “Do you really love Pittsburgh?” And I thought about it. It is a remarkable city filled with remarkable people. We have a lot to be proud of and a lot to love – beautiful parks, wonderful foundations and nonprofits, elected leaders and public servants who, for the most part, work hard on behalf of their constituents, noteworthy universities, an economy that, though once flat-lining, seems to have recovered. And our family has a remarkable community of friends who we really on consistently. We are a city that has bounced back through ingenuity, perseverance, and dedication to create the high tech / eds & meds / green urban core I know.

But, then I stop myself. That’s the city that I know, but so many know a different Pittsburgh. One that has withheld its opportunities. One that has reinforced segregation. Incarcerated its young men. Failed to adequately educate its children. Stood by as its physical and sometimes, its social structures, collapsed. Failed to invest in its communities, or clean up its parks, or repair its roads and sidewalks. And one that points a finger when people don’t work, but still won’t give them the chance to work in jobs that pay them enough to live. Can I truly love a City that doesn’t love all of its people equally?

It’s not that I didn’t know this before I went away, so why am I bringing it up now? I think, that it had become such a habit to spout the statistics about racial inequity in Pittsburgh, that in that moment, when I stopped and looked around and grew embarrassed to be dissing my city, I missed the point. I should not be worried about whether or not I love Pittsburgh or that what I say may be embarrassing to the city, but rather, I should be horrified that the place I call home is a place that shines on some of its people while raining hardships on others, and that despite a lot of work by many, many good people to fix this, the structural inequity remains.

And I fear ending this essay here, because despite what I have written, I am an optimist, and I still believe we can change the trajectory of our city. What I do love is that there are so many of us, of all backgrounds, shapes, sizes, and races, who recognize that there is a bounty of work to be done. But every once in a while we need to pick our heads up from our work and remember how truly brutal it can be for some to live in our city, and then we need to ask ourselves, what more can we do – not just to make an individual’s life better, but to completely break apart the injustice of our system?

This is the final blog of a multi-part series written by Landforce Executive Director Ilyssa Manspeizer about her reverse exchange with Costa Rican nonprofit Nueva Oportunidad.

Funding for the reverse exchange program has been provided by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs via Meridian International Center as the implementing partner.

- https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml

- https://www.bls.gov/home.htm

- Unemployment data is for census tract 1302, not by zipcode. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_17_5YR_S2301&prodType=table

- http://pittsburghpa.gov/equityindicators/documents/PGH_Equity_Indicators_2018.pdf